Craig Sams Pioneering Carbon-Conscious Practices in Food and Forestry

Episode Overview

Episode Topic

In this episode of Timber Talks, we delve into the world of sustainable forestry practices with Craig Sams, the Executive Chairman of Carbon Gold Limited. Craig shares his journey from the organic food industry to becoming a pioneer in the biochar and soil health sector. He discusses the origins of Carbon Gold and how the company has become a leader in promoting biochar as a critical tool for enhancing soil fertility and supporting sustainable agriculture. The conversation also touches on the broader implications of biochar for climate change mitigation and the evolving landscape of sustainable forestry.

Lessons You’ll Learn:

Listeners will gain valuable insights into the benefits of biochar, particularly its role in supporting the soil microbiome, enhancing soil fertility, and aiding in carbon sequestration. Craig explains how biochar helps retain soil nutrients and moisture, making it an essential component for sustainable forestry and agriculture. The episode also explores the emerging technologies and practices that are transforming the forestry industry, including the use of biochar in urban tree planting, agriculture, and even road construction. Additionally, Craig discusses the importance of carbon pricing and the potential future of biochar in global environmental strategies.

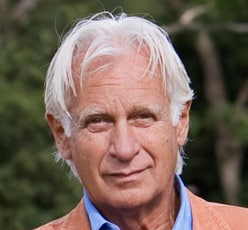

Craig Sams is the Executive Chairman of Carbon Gold Limited, a company at the forefront of biochar and sustainable soil solutions. With a background in organic food, Craig transitioned into the world of sustainable forestry after realizing the profound impact of soil health on climate change. He has been instrumental in promoting the use of biochar in various industries, from agriculture to urban planning. Craig is also a former chairman of the Soil Association and has been a vocal advocate for carbon pricing as a means to incentivize sustainable farming and forestry practices. His innovative approach to soil health continues to influence global discussions on sustainability.

Topics Covered

This episode covers a range of topics related to sustainable forestry and biochar. Craig Sams discusses the origins of Carbon Gold and the company’s mission to promote biochar as a tool for soil health and carbon sequestration. The conversation explores the science behind biochar, its benefits for soil microbiomes, and its applications in agriculture and urban forestry. Craig also highlights the importance of regulatory frameworks like carbon pricing in driving sustainable practices. Additionally, the episode touches on the potential future of biochar in global environmental strategies, including its use in construction and even space exploration.

.

About the Guest: Craig Sams Executive Chairman Carbon Gold Ltd

Craig Sams is a visionary entrepreneur and pioneer in the fields of organic food and sustainable agriculture. He co-founded Whole Earth Foods, a company that championed the organic food movement in the UK and brought natural, healthy products like organic peanut butter and cornflakes to the mainstream. Craig’s journey into sustainability didn’t stop at food; he later co-founded Green & Black’s, an organic chocolate company known for its commitment to ethical sourcing and environmental stewardship. Under his leadership, Green & Black’s became the first company to launch a product certified as carbon neutral, highlighting Craig’s dedication to reducing the environmental impact of food production. His early adoption of carbon-conscious practices set a precedent that continues to influence the industry today.

Transitioning from organic food to forestry, Craig founded Carbon Gold Limited, a company that specializes in biochar—a form of charcoal used to enhance soil health and sequester carbon. Craig’s interest in biochar was sparked by the discovery of terra preta, an ancient soil enrichment technique used by indigenous peoples in the Amazon. He recognized the potential of biochar to improve soil fertility, retain moisture, and reduce nutrient runoff, making it a vital tool in the fight against climate change. Today, Carbon Gold is at the forefront of promoting biochar in agriculture and forestry, offering sustainable soil solutions that support long-term environmental health. Craig’s innovative approach has positioned him as a leading figure in the sustainable forestry sector.

Beyond his entrepreneurial ventures, Craig has played a significant role in shaping the broader sustainability agenda. As the former chairman of the Soil Association, the UK’s leading organic certification body, he has been a vocal advocate for organic farming, carbon pricing, and sustainable land management. His work with the Soil Association helped to elevate the importance of soil health in the public consciousness and pushed for policies that recognize the environmental benefits of organic farming. Craig’s contributions to sustainability extend beyond business; he is a thought leader who continues to influence global discussions on environmental stewardship and the role of agriculture and forestry in mitigating climate change.

Episode Transcript

Mindy: Welcome to another episode of Timber Talks, the podcast, where we dive deep into the world of forestry and arboriculture. I’m your host, Mindy, and today we have a very special guest with us, Craig Sams, the Executive chairman of Carbon Gold Limited. Craig has been a pioneer in sustainable forestry practices, and his company is at the forefront of innovations and biochar and soil health. Welcome, Craig. Can you tell us about the origins of carbon, gold and the journey towards becoming a leader in biochar and sustainable soil solutions? And I would also like to add, could you define what biochar is for our listeners?

Craig Sams: Okay. First of all, my background isn’t in forestry. It’s in food, and that’s mainly an organic food. And I didn’t really start working with trees until I was moved on from my peanut butter business, which was called Whole Earth, to my chocolate business, which was called Green and Blacks. And suddenly I was dealing with a tree crop, cocoa beans. In the days of my food business, I launched a brand of corn flakes called Whole Earth, and we also launched a brand, Organic Corn Flakes. And we discovered that we didn’t have to pay for many carbon credits because the corn was grown organically and the farmers added carbon to the soil every year. Where they grew the corn, and that offset almost the rest of the carbon footprint of making the corn flakes, packaging them and shipping them, distributing them. And that’s when I realized that organic farming certainly is a way of dealing with the challenge of climate change. And I was the treasurer and then chairman of the Soil Association, which is our organic body here. And,, so I pushed for us to campaign for carbon pricing because, you know, if you’re an organic farmer, the big problem you have is people say, oh, organic food is too expensive. The minute you price in carbon. Organic food in most cases would actually be cheaper.

Craig Sams: That made me aware of the importance of carbon. Then I read a book that described terra preta, which is something they found in Brazil in what used to be before the Amazon rainforest took over the Amazon farming district of South America. In other words, the people there in their finding it. Every time they clear the rainforest, they find evidence that there were farmers there and they were making biochar out of all kinds of waste. They just dig a pit in the ground, throw in their food, waste any other waste, woodland waste, set fire to it, burn it without letting oxygen in. In other words, making charcoal. But the instead of burning the charcoal like like we do in barbecues or whatever, they would spread it on their lamb and it created these fertile patches of land in Brazil, where farmers would actually just sell truckloads of their soil to neighbors who didn’t have that kind of land because of the difference it made to fertility. So that’s when I thought, well, there’s this is something that should be marketed to farmers and growers in Britain. And so I founded a company called Carbon Gold, and we launched a range of products that were based on biochar. And basically biochar is charcoal.

Craig Sams: It’s ground up fine so that it really penetrates the soil. And once it’s in the soil, it has various benefits. The main one is it supports the mycorrhizal network in the soil. This is the microbiome of the soil. All the little fungi and bacteria that make for healthy soil. It also retains water. It helps to reduce the runoff of water, which often when you have runoff of water, you have runoff of the soil nutrients as well, which you don’t want to lose. And to support that, it has something called cation exchange capacity. So the biochar itself has lots of positive and negative points on it that stick to nitrates and phosphorus and other soil nutrients so that they don’t wash away when it rains. So when you put it in the soil, you are building up that mycorrhizal community, which ultimately fungi are not immortal. Bacteria are not immortal. When they die, their bodies, their cells become carbon as well. They break. So you build up soil organic matter more rapidly if you have biochar in the soil. So you’re building up long term fertility at the same time as you’re hanging on to the soil nutrients and to moisture. So that’s the difference between biochar and the charcoal that you might barbecue your sausages with.

Mindy: Okay. Well, in the US we we’ve been playing around with the carbon credits and stuff like that, but that really hasn’t. I know Europe with the ESG is you know, they have goals and stuff established. But in the US we’re typically slow at adopting some new ideas as far as agriculture or forestry goes. How has the forestry industry evolved over the years in terms of sustainability and environmental impact.

Craig Sams: Both up and down at the outset? You know, one of the things that’s happening in Europe at the end of this year is what’s called the UDR, which is the EU regulation on deforestation free products. So there’s going to start to be more control over food produced in the EU and important to the EU to make sure that there’s no deforestation associated with it., I founded a chocolate business in the farmers use bio char. They make their own, but an awful lot of cacao comes from deforested land. And because the stuff we use is organic, it’s the trees have shade trees to keep them healthy. But modern sort of ethnically chemically advanced cacao production uses chemical sprays to fight fungal diseases like black pod. And then you end up with the degraded soil and the need for more chemical fertilizer. Now the Forestry Stewardship Council and something called the Pefc program for the Endorsement of Forest Certification are both rising up the agenda. In Britain. We have the UK Woodland Assurance standard as well, the Soil Association, which I used to be chairman of, and I’m still on the board of the certification part.

Craig Sams: It’s a charity, but it has a certification business now certifies woodland to that standard and is rapidly expanding its role in certifying sustainable woodland and forestry and the associated products. And I think that’s the future. And the more that there is a legal requirement that deforestation doesn’t happen, the more it’s not going to happen. On the other hand, we still in Britain import huge ship loads of woodchips from Louisiana., that comes from forests in Arkansas that are planted, harvested, turned into woodchips, shipped to Britain. A wood pellets, I should say shipped to Britain and burned in a power station called Drax up in Yorkshire, where all the carbon that those trees have sequestered over the previous 30 years ends up back in the atmosphere in a couple of days. ,, to generate electricity and it you know, when you take into account that carbon footprint, it would be better to use oil, gas anything than wood. But. It’s renewable. And for a while that was what everybody wanted. Right, right.

Mindy: Could you give us some examples of the innovative technologies and practices that Carbon Gold has implemented to improve soil health and carbon sequestration?

Craig Sams: Sequestration? Yes. Yes. The. Well, one of the things we’re quite excited about is the Stockholm tree pit method. Mhm. I don’t know if you’ve heard of it.

Mindy: No I haven’t.

Craig Sams: Well, Bjorn Hembrom was the chief environment officer of Stockholm in Sweden. He developed something called tree pits where he would just put crushed granite into a sort of framework. And the urban trees, I mean, if you’re a tree in town, you’ve got to deal with the fact that they’re building, sticking up, that are getting in the way of your sunlight. There are cars and trucks rbling away, causing vibration that rattles your roots. The polluting and noise and not a lot of fertility. Bjorn started by using crushed stone crushed granite. He now adds bone. Stockholm is there that pioneered it. They add our biochar mix, which also has worm casts, seaweed powder for trace minerals, mycorrhizal fungi and something called Trichoderma. So you get a really strong biology with the biochar. The trees don’t need any other. They. Well, somebody asked Bjorn. So where is the soil in all of this? He says, don’t worry. The microbes will make the soil. It’s absolutely right, you know, the soil builds up as the trees get bigger. And it’s now being adopted in London, in Bristol, in New York, in quite a few towns in the UK. Now, people are planting urban trees because it means they last longer and they grow better in that sort of thing. So we’re quite excited about that. We also supply fruit growers. So there’s a apple grower in Shropshire up north, planted 2000 apple trees a few years ago. He expected, you know, normally 10 to 15% don’t quite make it. The only apple tree of those 2000 that didn’t make it was the one that he accidentally ran over with his tractor.

Craig Sams: But otherwise they all established they started fruiting earlier than he expected. We cocoa farmers that we work with in Belize, we gave them a couple of kilns so they could make their own biochar, and they now use it on cocoa production. And it’s pretty much having it in the soil has eliminated Black Spot, which is the curse of cocoa growers, because a beautiful cocoa pod suddenly develops this fungal infection and you can’t, you know, you just have to throw it away and hope that the rest of the tree isn’t infected. So those are the kind of examples of the kind of success we’ve had with trees. It really makes a difference in connecting a tree to the biology, the soil microbes, the biology, the microbiome, the biology of the soil and the. Once the tree is connected to that, it has a whole army of microbes on its side, bringing it food, giving it medicine, dealing with,, any problems that tree might have. And in exchange. Drawing down through the mycorrhizal fungi. Some of the carbohydrate, you might say, sugars that the tree is making by photosynthesis in its leaves. So the tree uses some of that to grow more branches more, leaves, more seeds, but it also uses that pp some of it down into its ridge system to feed that fungal network in the soil. And biochar really supports that fungal network.

Mindy: Okay. What upcoming technologies or practices do you believe will have the biggest impact on sustainable forestry?

Craig Sams: I think we’ve got most of the technology. What we have is a emerging regulatory system that makes the difference. The other thing that is really coming up fast now is that satellites can measure soil carbon. What You you still validate it by doing sampling in the traditional way. But you can then say, okay, when the satellite measures this, it’s 90% of the true figure or head over. This is the true figure, but you then calibrate it so that you get an exact figure. We are coming rapidly towards carbon pricing. And I think that’s going to make such a big difference for forestry and for farming. Once we know that the numbers were getting are true. It’s going to make a big difference to how people manage forests. One of the ways is you will get more mixed broadleaf type woodland. You know, it won’t all just be conifers. , there’s still a role for conifers and they play their part. But when soil carbon and biodiversity rise up the agenda, then people are going to respond. Now, if you’re a farmer growing wheat or barley, you can respond in a couple of years just by adopting more organic regenerative farming methods. Trees have a longer time scale. You know you can’t just change the way of a forestry establishment is in a year or two. It takes 20 years, 30 years, you know, you have to you have to think in a much longer term. But it’s it’s all going in the right direction. And, you know, when you get companies like Microsoft and other really major global companies who are saying, okay, we’re going to we’re going to start dealing with our carbon footprint. That’s probably the biggest single change.

Craig Sams: And it’s something that has been bubbling under, as I said. I mean, I launched those cornflakes. The first carbon neutral food product ever to be certified in 1994. So that’s 30 years ago. But the world has changed dramatically in the last 30 years. So I think that’s probably the the biggest single thing that identify. The other thing I think is happening there are skyscrapers. There’s one in Kyoto, in Japan. There’s a student dorm at the University of Vancouver. Buildings that are made out of wood but are like 50 stories high as I mean the house I’m in at the moment. Our house was built in 1770. Wow. It’s got an oak frame. It’s absolutely as long as we take care of the roof. We don’t have to worry. Nothing else goes wrong. My oak is a hardwood. Mhm. But I think. I think there is a movement more and more towards using wood in construction to lock carbon up in buildings. You know why? They have concrete and bricks and steel with a high carbon footprint if if it’s economic to use wood instead. So I think that’s an emerging market and we’re going to see a lot more of it the next few decades is some some of the examples are quite amazing really that you know how you can build a building. I mean, my house is I we’ve got we’re three storeys high, so there’s nothing particularly exciting about that. But when you get to 50 storeys and you’re still using wood as your framework, and in the case of Japan, where they have regular earthquakes, wood buildings can bend with an earthquake. They don’t fall apart in the way that concrete based ones do.

Mindy: How is carving goal preparing for these future changes and what new projects are you most excited about?

Craig Sams: We’re going in a couple of different directions. One is we have a range of products for gardeners, and we actually use this slogan saving the planet one garden at a time. , because if everybody who gardens, you know, people don’t take stuff out of their gardens that much, they tend to just grow stuff for their pleasure. , we have something now called no mow May, where people leave their garden alone for the month of May. And, you know, I’m looking out now at my window., you know, we have grass that’s nearly knee high. I think that we’ve gone for gardening, and people use it for growing vegetables and in greenhouses. Vertical farming is coming up. The agenda now by Charles. Very helpful in hydroponics. It keeps your nutrients in the flow. So we’ve got we’ve got that the and of course these I mentioned the Stockholm tree pit method that’s really taking off now because it’s you know when you’re planting trees, you want to you’re thinking 30, 40, 50 years ahead. So you want trees that are going to still be trouble free in 30 or 40 or 50 years. We’re shipping more and more of our product to places like Qatar and Dubai in the Gulf, the sort of countries which are desert but actually are only desert because goats and sheep were prioritized and they overgrazed. And then gradually the vegetation died away, the soil lost its fertility, and the quickest way to rebuild that fertility is to get biochar, or particularly enriched biochar, which is what we make at carbon gold.

Craig Sams: And, , you know, the Cop 28, the last climate conference, I was a speaker there, and they had an urban farm, an example of sustainable carbon sequestering farm. And they had our biochar product throughout it in the soil. And it makes a big difference. So I think that’s another area where we see a lot of growth in the Middle East and anywhere where soil needs remediation. Funnily enough, biochar char also ends up in asphalt. You know, it’s especially with electric cars. You get more potholes, like holes in asphalt roads that people swerve to avoid, and then they run into an oncoming car. If you put bio char into asphalt, it strengthens it and you get a much more resilient service. California is now leading the charge on that. Yeah. In terms of getting buy chart into road building. It also goes into concrete. And I mentioned in buildings, but really the sort of the areas where we’re seeing the most growth is gardening, because people want it in their own gardens, because it makes a difference. Vegetable growers, they they’re seeing the commercial benefits. You know, they can use less manure or compost or fertilizer if they have by chart in the soil. And,, there is a,, we’re working with some people who are going to be at the,, it’s in Lincoln, Nebraska in September, and it’s a Great Plains bio char control that it’s the first one, but they’re they’re the Nebraska State. I was born in Nebraska.

Mindy: Oh.

Craig Sams: I’m quite proud about this, this development. But the Great Plains Biochar Conference, the,, Nebraska Forestry Service participating and supporting it because,, the prairies that. Well, as I said, I was born in Nebraska. My great grandfather plowed prairie that had 250 tons of carbon per hectare.. What’s that? About 100 tons per acre. By the time I was born, that was down to ten. Wow. Rest ended up. Most of it ended up in the atmosphere, but then the soil structure broke down. And as that happened, and in 1927, it rained and it the soil just gave way. And you had flooding down in,, Missouri and Arkansas, where all that farmland from places like Nebraska and South Dakota and Iowa just washed away. And that’s why there wasn’t any carbon in the soil or hardly any by the time I was born. You may have heard of Muddy Waters. Well, he was named after a song called Muddy Waters, and there was a whole slew of blues songs from all those farmers in the who, you know, got 40 acres and a mule when they were freed from slavery after the Civil War and they got washed out. All right. The they ended up in Detroit or Chicago working in car factories, but it wasn’t what they had expected. So there’s plenty of room to rebuild those rich prairie soils the Pawnee used to use biochar. The tribes of Pawnee in Nebraska would create biochar out of prairie grass. The following year, the buffalo would all graze in that area, and the Pawnee had created drive lines. They could, even though they didn’t have horses or guns, they could stampede the buffalo down the drive lines because they were all congregated there, and they would chase them off the edge of a cliff and down below the teepee makers, the clothing makers and the food processors, the butchers are all there. But. So the biochar had a use in North America historically as well as in the Amazon. Well, it.

Mindy: Seems what I’ve been kind of seeing as what is old is new again, we seem to to become a circling back around to some old techniques that that worked because we, at least in North America, we’re kind of seeing are we seeing what we’ve done to the environment and how we’ve been responsible for that? Because when I teach, , I was teaching classes for senior citizens through the AARP organization, you know, chemical application and all that stuff that I always tend to go in the organic way because it’s it’s kinder to the environment and it’s better for people. So but, you know, organic gardening hasn’t always been the, the big thing that it it is now. And unfortunately in North America some people don’t know what organic really means. So it’s sometimes it’s an education.

Craig Sams: What advice. Wendell Berry, his great quote,, he said we didn’t know what we were doing because we didn’t understand what we were undoing. And I think, you know, for my great grandfather, here was this miraculous land where you didn’t you just. You plowed it, you put in your grain, and you got these abundant crops every year, and it never seemed to run out. But then by 1930, while a few years later you had the dustbowl, the same thing happened. Not as bad as the dustbowl, but in Europe, you know, a lot of our soils are just. And they’re just not what they were. Melody. And, you know, we can’t use and do chemical fertilizers by you a bit more time, but ultimately you just have to keep using more and more to stay in place.

Mindy: Right, right. Well, in North America, you know, we’ve we are learning the lessons of but we’re really not doing much about it, about the cost of removing wetlands. You know, we have more flooding. We have like a Louisiana as an example. We’re we’re beginning to see the, the cost of that behavior. We know better. We just continue to one not adjust. And and two, I guess some ways that’s just han nature. But I love Wendell Berry. I’m very familiar with him. So okay. What are the common issues that forestry professionals face when it comes to soil health. And how can biochar help mitigate these issues?

Craig Sams: Well, I think the issues you’re talking about are ecosystem services. You know, forest isn’t just somewhere where you get wood sequesters carbon. It purifies the air that we breathe. It reduces the risk of flood. And it’s good for han health and sanity just to, you know, be in or around woods. And the fact if you add it all up, you’re the real value from an ecosystem point of view is sometimes even more than the value of the wood that you harvest from it. I think that’s what we call natural capital, public money for public goods. And it’s something that we don’t, you know, we don’t pay people who grow trees, who have woodland for the fact that they’re making our air cleaner or, you know, more oxygen. We don’t pay them. Well. We have a group here. I have 20 acres of woodland. My neighbors are quite small, most of them 48 years. A few farmers. We had terrible flooding in January of this year. Where near the sea and the people who are down in what used to be the marshes and got drained, they all got flooded. And it was really, really sad. Some of the stories of what happened were all now working together. We call it the Future Landscapes Trust, but we’re working because part of it we’re putting in what are called,, they’re like log dams that just slow the flow of water so that it doesn’t. Just when it rains, it doesn’t rush off because we’ve got hills leading down to the sea. So when it rains, the water, you know, gravity being what it is, the water washes down and,, and the people near the sea take the hit. So that’s these are all economic things that, you know, never got calculated when people were just talking about wood and wood as fuel even. Yeah, even more so. Nobody thinks about the impact on climate of burning wood.

Mindy: Right. Well, I see, you know, in North America we have, you know, this kind of divide on forests, you know, multi-use type of approaches. And, you know, everybody, you know, their opinion is the top of the pile, so to speak. So and we always have, you know, somebody wants to cut our national forests in some way, you know, take a million acres as an example and harvest it just, you know, like it’s it’s a disposable product and it is to away. But forest in the in our environment is so important to our health. I mean science is proving that over and over and over again. So there’s a local story of a gentleman. They actually named a park after him. And it was in the 1930s, and he was sick, and he kept going to his doctor, and his doctor said, I don’t know what’s wrong. All I can suggest is you spend 30 minutes a day in the forest. And so he did. That felt better. He started increasing the amount of time. He ended up being a naturalist and talked and taught people, you know, and the 1930s how being in a forest can actually make you healthier. And, you know, it’s a continuing education in my in my neck of the woods of educating people of of the value of a tree versus, you know, the beauty, the wood, what it does for our environment and what it does for us as hans. And I think that’s kind of a new concept, that trees have that type of value. It helps us stay healthy and that type of thing. So, .

Craig Sams: Well, there is a book called 13 Ways to Smell a Tree. Where is it? It captures some of what you’ve just described. There is also a book by a guy called Jake Robinson that I recommend to everybody. It’s called Invisible Friends and it’s about the. It’s not just oxygen. The trees are exhaling into the air. Every tree from their leaves. It’s all kinds of therapeutic chemicals called terpenes. Pinions. Fir trees and pine trees. And these have a real benefit. I’ll be involved with trees. And so we,, you know, if you go back far enough in han history, we were monkeys living in trees. And the benefits of tree exhalations are really hard to measure. But they are. I go for a walk out my back door. I live in a valley that faces the sea. So all the stuff that trees exude, the breezes when the wind comes over. It doesn’t. Unless it’s coming directly from the southeast. It when it blows it away inland. The rest of the time it just goes over it. So it kind of acculates here. I just go for a walk and just take a deep breath, stand still.

Craig Sams: Sometimes I’ll bunch up some leaves of a tree. Just take a deep breath and you’re getting all that stuff that’s just sitting on the leaves waiting for someone to grab it. Somebody put a value of in sterling 2.79 pounds. For every pound of that you get from woodland. So, in other words, the real value of a woodland is actually almost three times the value of the wood itself because of the benefits for water quality, air quality, soil quality. , we dug a we’ve put a wildlife pond in our garden here, which is on a slope or on a hill, which was forest for until this house was built, as I said, 270 years ago. And we wanted the water. We just thought it would be a nice little pond that would be two feet deep. Well, the guys who did it said we have to get down to the clay. We have to get down to some kind of subsoil. And they had to go find more than five feet.

Mindy: Wow.

Craig Sams: The trees have just over the millennia. Every time the leaves drop, they decompose. And we got more soil. And we have this deep, rich soil that, you know, is gold dust. Really? Yes.

Mindy: Yes. I totally agree with you. , and people don’t, don’t really realize that soil is really like gold dust because we would be really hurting if if we didn’t have soil. And the soil has served us well, but we as a species haven’t always served soil well either. So, you know, it’s hopefully we’re seeing a change, a global change. I know that the change has to start somewhere. But I mean, in North America, farmland is getting and woodlands getting be absorbed for urban development. Like it’s, you know, an unlimited resource. And it’s not it is a limited resource and just some bad, , what I would consider some bad urban planning. But you know, again, that that will be a lesson that we have to learn. Unfortunately, in North America, I think we’re a little slow in those lessons.

Craig Sams: So North America, you know, it’s,, everywhere. And they. I think I’m a big believer in carbon pricing. You know, farmers are businessmen. They count every penny. They they more than anybody else, they really from year to year, they depend on the economic impact of the weather, of the soil, of the market for what they produce. And if you put carbon into if you could put a price on carbon, people would farm in a more sustainable way. They would plant more trees on their land. I remember my uncle, he moved from Nebraska to Iowa, but he showed me a corporate farm that had an avenue of trees leading up to the farm buildings, and he said, I don’t get it. Why are these people growing these trees? Don’t they realize that the shade from those trees is going to reduce their yield by six bushels per acre all along that site? And of course, if you just look at the bushels per acre, they get rid of the trees. But, you know, there’s so many other benefits from trees, like holding the soil together and the network. I mean, you look at a tree, what you don’t realize is you can be 20ft away from it and you’re still standing on its roots, and the mycorrhizal network can go much further even than that. So it’s all happening. It’s just invisible.

Mindy: Right, right. What best practices should professionals follow to maximize the benefits of biochar and other sustainable technologies in their day to day operations?

Craig Sams: I think on the biochar there are it’s it’s good to put it in the ground when you plant trees. It also works with trees that aren’t well. So there are a lot of examples. We work with a company here called Apex Soil Solutions, and they have a device called the geo injector, which is going to be rolled out in the US next year. It’s a device that goes, it’s like a tube that goes into the ground. That is a compressor at the back, and it blows air sideways into the soil, so it compacts the soil. When you put biochar in with the mix that we have with the mycorrhizae and the worm casts, etc., that goes into the soil as well. We have a mulberry tree in our garden that has been there for a couple of hundred years, and it’s a huge tree, and it started getting little black spots on the leaves. We gave it the treatment with the geo injector, and I’m looking at it now and it’s absolutely blast. The first year after it was treated, there were just a few spots still on the leaves. Last year it was almost perfect this year so far. Touch wood. It’s it’s it’s still it’s really doing well. And so I think there are ways of getting, making existing trees healthy and there are ways of making trees of the future healthy by putting biochar in the ground before you plant them. Then the roots get away. They connect to the soil microbiome and you’re on a roll. You know that they’re away.

Mindy: Do you see? , I used to. I did a couple of projects for NASA where I grew tomato seeds. I grew tomatoes from seeds that went up into the International Space Station. I did the same with basil. And I know they took soil samples of the soil and Mars and and mimicked the soil here on Earth. , what would grow and everything that they planted, , vegetables, herbs, trees, etc. grew in this mimicking of Martian soil. Do you see way in the future biochar being,, a component of us, , growing food on other planets, that type of thing, using the same technology. , because I would, you know, bio char, , is probably a lightweight product. Would probably be lighter than soil.

Craig Sams: Have you been reading my mail?

Mindy: No no no no no no, I’m always, always curious.

Craig Sams: I am meeting on this coming Tuesday, the 16th of July with a company called Vertical Futures to do vertical farming. They are also working with the International Space Station on developing resilient growing systems. For that, I’m not sure we should mess around with the climate on Mars or the moon, but, you know, yes, I think forgetting about them, we’ve done enough to our landscape that needs remediation. There’s plenty of work getting our planet back into good soil. Help before we go into outer space. But that’s it. Just interesting because, you know, people are looking at that and looking at the role that biochar can play in that.

Mindy: Right? I’ve written three books that have to do with herbs and seeds Will travel. That’s what I tell people. Seeds will travel and if we can take every medicine with us. But that is an option to grow our own medicine, so to speak, to. But to be able to do that, we’re going to need some, some things. And I’m not an advocate of sending synthetic fertilizer to Mars. , but I was just curious because I know that’s kind of one of the limiting factors of growing our own food wherever we go, Mars or the moon or whatever, if that was, if that was something that was in the pipeline or, or an idea you had thought of or so. Well, that brings us to the end of the episode of Timber Talks. Craig, thank you so much for joining us today and sharing your insights on sustainable forestry practices and the future of the industry. It’s been a fascinating discussion, and to our listeners, thank you for tuning in. If you enjoyed this episode, please subscribe, leave a review and share it with your colleagues. Stay tuned for more episodes of Timber Talks, where we continue to explore the latest in forestry and arboriculture. Until next time, take care and keep innovating